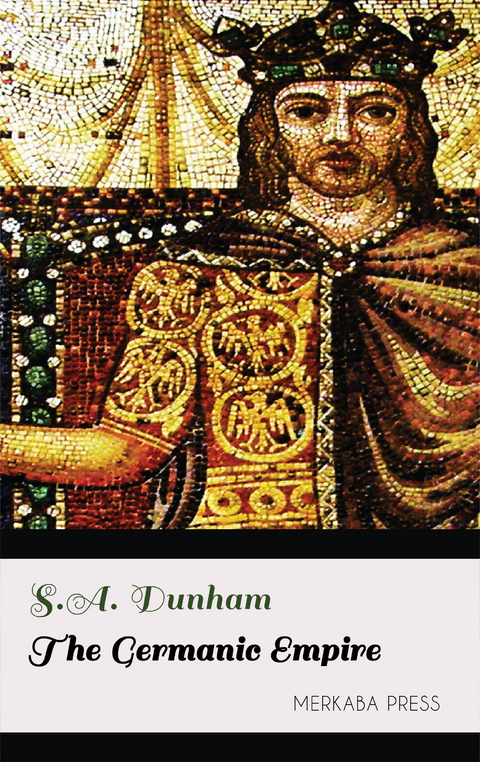

The Germanic Empire (eBook)

201 Seiten

Merkaba Press (Verlag)

978-0-00-001835-9 (ISBN)

With Germany prior to the dissolution of the Roman power, the present compendium has no concern: the history of that period is, or ought to be, familiar to every reader. Our object is to contemplate that celebrated country as an Empire; but as its establishment must be traced to an era considerably anterior, a few pages by way of introduction may properly open the main subject.

CHAPTER I. THE CARLOVINGIAN DYNASTY.

752—910.

CHARLEMAGNE RESTORES THE EMPIRE OF THE WEST.—HIS REIGN AND HIS IMMEDIATE SUCCESSORS.—CONVULSIONS OF THE EMPIRE.—CIVIL WARS.—SEPARATION OF THE FRANK AND GERMANIC CROWNS.—GOVERNMENT, LAWS, SOCIETY, AND MANNERS OF THE GERMANS DURING THE DOMINATION OF THIS HOUSE.—LAWS THROWING LIGHT ON THAT SOCIETY.—CODES OF THE FRANKS.—BURGUNDIANS. —SWABIANS.—BAVARIANS.—ANGLES.—SAXONS.—FRISIANS.

The conduct of Pepin was not unworthy of the confidence which had been reposed in him. Like his immediate predecessor, he triumphed over the hostile Frisians and Saxons, and he quelled the insurrections of the Germanic dukes. To the pope he proved that he could be grateful for his elevation to a throne. Being honoured by a personal visit from Stephen III., and informed of the extremity to which the Roman possessions were reduced, he first remonstrated with Astolfus of Lombardy; and when that prince still marched on Rome, he hastened into Italy, and forced him to restore the exarchate of Ravenna, not indeed to the Greek emperor, but to the pope. In his testament, which he took care to see confirmed in a public diet, the year before his death, he left his two sons, Charles and Carloman, joint heirs of his states. To the one he left the West, from Frisia to the Pyrenees; to the other, the Germanic provinces, part of Austrasia, Alsace, Switzerland, Burgundy, and Provence. To us, whom history has presented with a wide field of experience, it often seems surprising that such impolitic measures could be adopted by men distinguished for considerable powers of judgment,—for such, assuredly, were Charles Martel and Pepin. Its ruinous effects were before the eyes of both; yet neither they nor any other sovereign of these ages ever thought of deviating from it. It is indeed probable, that to one of the sons,—generally the eldest,—a superiority was awarded over the others; but it was merely feudal,—consequently nominal. The most obvious cause of this policy must be traced to that natural affection, and to those natural feelings of justice, which lay in the paternal breast; yet a more enlightened affection would have shrunk from placing sons in a position where they must inevitably become hostile to one another,—where troubles must, of necessity, agitate both them and their people. But the equality of rights among the children of the same family, the total absence of primogenital advantages, distinguished all the Teutonic, all the Sclavonic nations; and custom was too powerful to be eradicated by policy, until it was found, by that most effectual, though most melancholy of teachers, experience, that where primogeniture is not adopted, society will be disorganised. In the present instance, indeed, no serious mischief followed the partition. A civil war was preparing by both brothers, when Carloman died, and though he left children, their claims were disregarded by Charles, who seized the whole inheritance.

In estimating the reign and character of Charlemagne, let us not lose sight of the peculiar advantages which at- to tended his accession. 1. He was the undisputed master of France, for the Arabs had, in the late reign, been driven from Septimania. In Germany he had ample possessions, and if he could place little dependence on the attachment of the Bavarians, the Franconians were bound to his government, and the Swabians were not ill affected towards him. His empire, therefore, extended from the Scheldt to the Pyrenees, and from Bohemia to the British Channel. 2. The forces, to the direction of which he also succeeded, had been rendered warlike and confident by the victories of his father and grandfather. 3. He had nothing to fear from the Arabs, whom his great predecessor had taught for ever to respect the territory of the Franks; nor from the Lombards, who could not for a moment contend with him; nor from the Greek empire, which was fast sinking into imbecility. 4. The north had not yet equipped the formidable maritime expeditions which, in another century, were to shake Europe to its foundations. 5. The introduction of Christianity, during the eighth century, into Germany, in some degree, even among the Saxons and the Frisians, opened the way for greater triumphs; since the new converts were taught to pray for the success of the Christian king,—of one who would prostrate the idols of the Pagans, burn the temples so long polluted by bloody rites, and infuse a new spirit, the spirit of harmony, of peace, and happiness, into scenes which had long been disfigured by the tempest of passion and of violence. These were great advantages, the coincidence and concurrence of which nothing short of Omniscience could have foreseen, perhaps which nothing short of Omnipotence could have produced. Yet he had difficulties to remove which would have cooled the ardour of any other prince. The Frisians and Saxons were, in the proportion of nine to ten, pagans, actuated by a fierce hatred of Christianity, and by a quenchless thirst for blood and plunder. These were men to whom war was agreeable as a passtime, and whose predatory incursions had for ages troubled the surrounding tribes. We are astonished to see the territorial progress of the Saxons. At the dissolution of the Western empire, they occupied, as we have before shown, a bounded region near the mouth of the Elbe. Now they bordered on Franconia to the south, westward with the Frisians, and eastward with the Sclavonic tribes, which lay between the Elbe and the Oder. This aggrandisement was the effect, not so much of increase in population,—for barbarous nations do not multiply,—as of conquest. They forced other tribes to amalgamate with them, and their augmented number of warriors enabled them to meditate even greater enterprises than they had yet effected. Again, the Bavarians bore their dependence on the Franks with exceeding impatience; they waited only for a rising in northern Germany, to throw their own swords into the scale of war. Should they and the Saxons combine, it would require all Charlemagne’s power to break their force. From the very commencement of his reign he seems to have meditated the subjugation of both. He began with the Saxons, the most formidable and savage of his enemies; and though his operations were often suspended by his campaigns in Spain, Aquitaine, and Italy, he always returned with augmented vigour to the charge. In 772 war was formally declared against them, in the diet of Worms. The immediate cause was, the massacre of some missionaries whom the monarch had sent to reclaim the people from idolatry, but their frequent irruptions in Franconia had no less effect on the resolution. In a rapid campaign, he prostrated these ferocious people; for what could undisciplined, however brave levies effect, in opposition to a veteran army, led by one of the ablest generals that Europe has ever produced? In this campaign he took the strong fortress of Eresberg (now Statbergen, in the bishopric of Paderborn), containing the temple and idol of Irminsul, (statue of Irmin), the object of their peculiar veneration. This Irmin was the celebrated Arminius (Armin), the Cheruscan (a branch of the Saxons) chief, who, eight centuries before, had cut off the Roman army, with its leader Quintilius Varus. That such a hero should long be venerated as the saviour of his country; that in the progress of centuries he should attain the honour of deification, is exceedingly probable. All the pagan demigods have, at some period, been men, whose fame, magnified through the mist of succeeding ages, has been elevated from human to divine. Such was Hercules, such Odin, such Armin. After this triumph, Charlemagne halted on the banks of the Weser, arid forced the deputies of the Saxon states—the chiefs of the confederation,—to give hostages for their future obedience. In a short time, however, so far from observing the treaty, they poured their wild hordes into Franconia, burnt every church and monastery that fell in their way, and put every creature to the sword. Another campaign reduced the four great tribes, or rather confederation of tribes, of” which they were composed,—the Westphalians, who lay west of the Weser; the Eastphalians, who lay between that river and the Ems; the Angravarians, who bordered the Westphalians; and the Nordalbingians, who dwelt north of the Elbe, the cradle of the Saxon race. As before, however, no sooner was he engaged in a distant war, than they renewed their depredations; and, on his return, were forced to bend before his commanding genius. He soon discovered that these savage people could never be civilised, never be made to forsake their warlike habits, unless they were effectually reclaimed from idolatry. With this view, he dispersed the numerous hostages he received in the cloisters of monasteries, and sent missionaries to labour in the wide field. In 776 Witikind, the most famous chief of the Saxon chiefs, instigated the Westphalians to revolt; and committed ravages which long rendered his name memorable; but the monarch’s approach compelled him to seek shelter with the Danish king. Charles had reason enough to be dissatisfied with his two great feudatories, the dukes of Swabia and Bavaria, who during his absence raised not a lance in defence of the invaded provinces. When, in 778, Witikind returned, duke Tassilo of Bavaria remained inactive: (the troops of Swabia appear to have been...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.7.2017 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte |

| ISBN-10 | 0-00-001835-X / 000001835X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-00-001835-9 / 9780000018359 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 822 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich