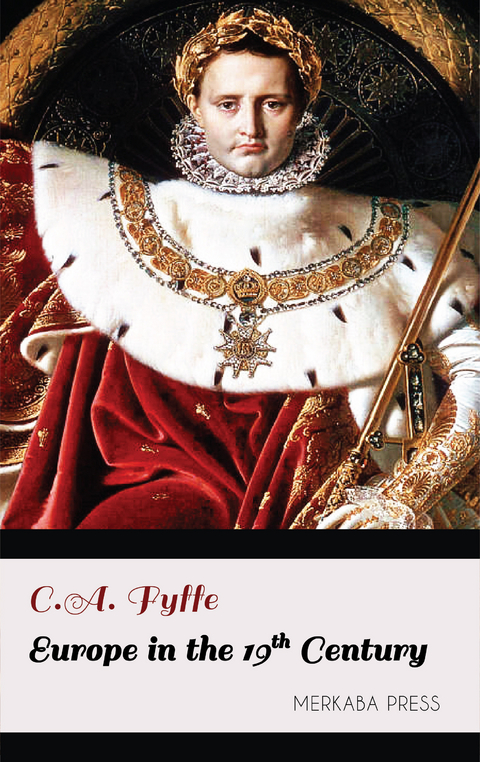

Europe in the 19th Century (eBook)

768 Seiten

Merkaba Press (Verlag)

978-0-00-001851-9 (ISBN)

On the morning of the 19th of April, 1792, after weeks of stormy agitation in Paris, the Ministers of Louis XVI. brought down a letter from the King to the Legislative Assembly of France. The letter was brief but significant. It announced that the King intended to appear in the Hall of Assembly at noon on the following day. Though the letter did not disclose the object of the King's visit, it was known that Louis had given way to the pressure of his Ministry and the national cry for war, and that a declaration of war against Austria was the measure which the King was about to propose in person to the Assembly. On the morrow the public thronged the hall; the Assembly broke off its debate at midday in order to be in readiness for the King. Louis entered the hall in the midst of deep silence, and seated himself beside the President in the chair which was now substituted for the throne of France. At the King's bidding General Dumouriez, Minister of Foreign Affairs, read a report to the Assembly upon the relations of France to foreign Powers. The report contained a long series of charges against Austria, and concluded with the recommendation of war. When Dumouriez ceased reading Louis rose, and in a low voice declared that he himself and the whole of the Ministry accepted the report read to the Assembly; that he had used every effort to maintain peace, and in vain; and that he was now come, in accordance with the terms of the Constitution, to propose that the Assembly declare war against the Austrian Sovereign. It was not three months since Louis himself had supplicated the Courts of Europe for armed aid against his own subjects. The words which he now uttered were put in his mouth by men whom he hated, but could not resist: the very outburst of applause that followed them only proved the fatal antagonism that existed between the nation and the King. After the President of the Assembly had made a short answer, Louis retired from the hall. The Assembly itself broke up, to commence its debate on the King's proposal after an interval of some hours. When the House re-assembled in the evening, those few courageous men who argued on grounds of national interest and justice against the passion of the moment could scarcely obtain a hearing. An appeal for a second day's discussion was rejected; the debate abruptly closed; and the declaration of war was carried against seven dissentient votes. It was a decision big with consequences for France and for the world. From that day began the struggle between Revolutionary France and the established order of Europe. A period opened in which almost every State on the Continent gained some new character from the aggressions of France, from the laws and political changes introduced by the conqueror, or from the awakening of new forces of national life in the crisis of successful resistance or of humiliation. It is my intention to trace the great lines of European history from that time to the present, briefly sketching the condition of some of the principal States at the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, and endeavouring to distinguish, amid scenes of ever-shifting incident, the steps by which the Europe of 1792 has become the Europe of today...

Chapter I

Outbreak of the Revolutionary War in 1792-Its immediate causes- Declaration of Pillnitz made and withdrawn-Agitation of the Priests and Emigrants-War Policy of the Gironde-Provocations offered to France by the Powers-State of Central Europe in 1792-The Holy Roman Empire- Austria-Rule of the Hapsburgs-The Reforms of Maria Theresa and Joseph II.-Policy of Leopold II.-Government and Foreign Policy of Francis II.-Prussia-Government of Frederick William II.-Social condition or Prussia-Secondary States of Germany-Ecclesiastical States-Free Cities-Knights-Weakness of Germany

On the morning of the 19th of April, 1792, after weeks of stormy agitation in Paris, the Ministers of Louis XVI. brought down a letter from the King to the Legislative Assembly of France. The letter was brief but significant. It announced that the King intended to appear in the Hall of Assembly at noon on the following day. Though the letter did not disclose the object of the King's visit, it was known that Louis had given way to the pressure of his Ministry and the national cry for war, and that a declaration of war against Austria was the measure which the King was about to propose in person to the Assembly. On the morrow the public thronged the hall; the Assembly broke off its debate at midday in order to be in readiness for the King. Louis entered the hall in the midst of deep silence, and seated himself beside the President in the chair which was now substituted for the throne of France. At the King's bidding General Dumouriez, Minister of Foreign Affairs, read a report to the Assembly upon the relations of France to foreign Powers. The report contained a long series of charges against Austria, and concluded with the recommendation of war. When Dumouriez ceased reading Louis rose, and in a low voice declared that he himself and the whole of the Ministry accepted the report read to the Assembly; that he had used every effort to maintain peace, and in vain; and that he was now come, in accordance with the terms of the Constitution, to propose that the Assembly declare war against the Austrian Sovereign. It was not three months since Louis himself had supplicated the Courts of Europe for armed aid against his own subjects. The words which he now uttered were put in his mouth by men whom he hated, but could not resist: the very outburst of applause that followed them only proved the fatal antagonism that existed between the nation and the King. After the President of the Assembly had made a short answer, Louis retired from the hall. The Assembly itself broke up, to commence its debate on the King's proposal after an interval of some hours. When the House re-assembled in the evening, those few courageous men who argued on grounds of national interest and justice against the passion of the moment could scarcely obtain a hearing. An appeal for a second day's discussion was rejected; the debate abruptly closed; and the declaration of war was carried against seven dissentient votes. It was a decision big with consequences for France and for the world. From that day began the struggle between Revolutionary France and the established order of Europe. A period opened in which almost every State on the Continent gained some new character from the aggressions of France, from the laws and political changes introduced by the conqueror, or from the awakening of new forces of national life in the crisis of successful resistance or of humiliation. It is my intention to trace the great lines of European history from that time to the present, briefly sketching the condition of some of the principal States at the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, and endeavouring to distinguish, amid scenes of ever-shifting incident, the steps by which the Europe of 1792 has become the Europe of today.

The first two years of the Revolution had ended without bringing France into collision with foreign Powers. This was not due to any goodwill that the Courts of Europe bore to the French people, or to want of effort on the part of the French aristocracy to raise the armies of Europe against their own country. The National Assembly, which met in 1789, had cut at the roots of the power of the Crown; it had deprived the nobility of their privilees, and laid its hand upon the revenues of the Church. The brothers of King Louis XVI., with a host of nobles too impatient to pursue a course of steady political opposition at home, quitted France, and wearied foreign Courts with their appeals for armed assistance. The absolute monarchs of the Continent gave them a warm and even ostentatious welcome; but they confined their support to words and tokens of distinction, and until the summer of 1791 the Revolution was not seriously threatened with the interference of the stranger. The flight of King Louis from Paris in June, 1791, followed by his capture and his strict confinement within the Tuileries, gave rise to the first definite project of foreign intervention. Louis had fled from his capital and from the National Assembly; he returned, the hostage of a populace already familiar with outrage and bloodshed. For a moment the exasperation of Paris brought the Royal Family into real jeopardy. The Emperor Leopold, brother of Marie Antoinette, trembled for the safety of his unhappy sister, and addressed a letter to the European Courts from Padua, on the 6th of July, proposing that the Powers should unite to preserve the Royal Family of France from popular violence. Six weeks later the Emperor and King Frederick William II. of Prussia met at Pillnitz, in Saxony. A declaration was published by the two Sovereigns, stating that they considered the position of the King of France to be matter of European concern, and that, in the event of all the other great Powers consenting to a joint action, they were prepared to supply an armed force to operate on the French frontier.

Had the National Assembly instantly declared war on Leopold and Frederick William, its action would have been justified by every rule of international law. The Assembly did not, however, declare war, and for a good reason. It was known at Paris that the manifesto was no more than a device of the Emperor's to intimidate the enemies of the Royal Family. Leopold, when he pledged himself to join a coalition of all the Powers, was in fact aware that England would be no party to any such coalition. He was determined to do nothing that would force him into war; and it did not occur to him that French politicians would understand the emptiness of his threats as well as he did himself. Yet this turned out to be the case; and whatever indignation the manifesto of Pillnitz excited in the mass of the French people, it was received with more derision than alarm by the men who were cognisant of the affairs of Europe. All the politicians of the National Assembly knew that Prussia and Austria had lately been on the verge of war with one another upon the Eastern question; they even underrated the effect of the French revolution in appeasing the existing enmities of the great Powers. No important party in France regarded the Declaration of Pillnitz as a possible reason for hostilities; and the challenge given to France was soon publicly withdrawn. It was withdrawn when Louis XVI., by accepting the Constitution made by the National Assembly, placed himself, in the sight of Europe, in the position of a free agent. On the 14th September, 1791, the King, by a solemn public oath, identified his will with that of the nation. It was known in Paris that he had been urged by the emigrants to refuse his assent, and to plunge the nation into civil war by an open breach with the Assembly. The frankness with which Louis pledged himself to the Constitution, the seeming sincerity of his patriotism, again turned the tide of public opinion in his favour. His flight was forgiven; the restrictions placed upon his personal liberty were relaxed. Louis seemed to be once more reconciled with France, and France was relieved from the ban of Europe. The Emperor announced that the circumstances which had provoked the Declaration of Pillnitz no longer existed, and that the Powers, though prepared to revive the League if future occasion should arise, suspended all joint action in reference to the internal affairs of France.

The National Assembly, which, in two years, had carried France so far towards the goal of political and social freedom, now declared its work ended. In the mass of the nation there was little desire for further change. The grievances which pressed most heavily upon the common course of men's lives-unfair taxation, exclusion from public employment, monopolies among the townspeople, and the feudal dues which consumed the produce of the peasant-had been swept away. It was less by any general demand for further reform than by the antagonisms already kindled in the Revolution that France was forced into a new series of violent changes. The King himself was not sincerely at one with the nation; in everything that most keenly touched his conscience he had unwillingly accepted the work of the Assembly. The Church and the noblesse were bent on undoing what had already been done. Without interfering with doctrine or ritual, the National Assembly had re-organised the ecclesiastical system of France, and had enforced that supremacy of the State over the priesthood to which, throughout the eighteenth century, the Governments of Catholic Europe had been steadily tending. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which was created by the National Assembly in 1790, transformed the priesthood from a society of landowners into a body of salaried officers of the State, and gave to the laity the election of their bishops and ministers. The change, carried out in this extreme form, threw the whole body of bishops and a great part of the lower clergy into...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.7.2017 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte |

| ISBN-10 | 0-00-001851-1 / 0000018511 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-00-001851-9 / 9780000018519 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 944 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich