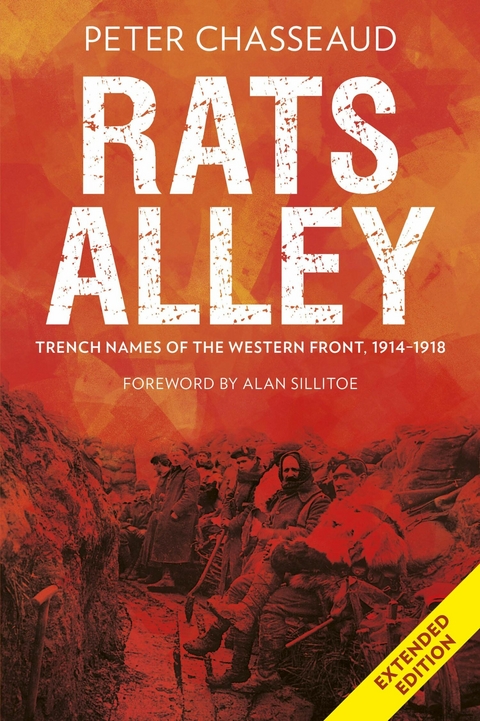

Rats Alley (eBook)

768 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7509-8490-4 (ISBN)

Dr PETER CHASSEAUD is the acknowledged expert on First World War survey and mapping, and an acclaimed military historian. He was a commissioner on the A19 (Ypres battlefield) project, and is involved in battlefield archaeology and research. In his long career, he has worked for TV and on the Naval and Military Press/Imperial War Museum/National Archives 1914-18 trench map CD and DVD projects, and has also published several books. He is a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and a member of the Royal United Services Institute.

Dr Peter Chasseaud is the acknowledged expert on First World War survey and mapping. He was a commissioner on the A19 (Ypres battlefield) project, and is involved in battlefield archaeology and research. He has worked for TV and on the Naval & Military Press/Imperial War Museum 1914-18 Maps CD project. He has also published several books and is an acclaimed military historian. He is a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and a member of the Royal United Services Institute.

I

TRENCHES AND THE LANDSCAPE

The first part of this chapter looks at how the trench system developed and became part of the landscape, while the second part examines the way in which the battlefield landscape and the natural world were perceived and mythologised by the troops, and the impact this had on trench naming. The following chapters follow the development of naming along the front, and focus on specific naming themes.

The Development of Trenches and Trench Systems

Early 18th-century plan of the siege of Béthune (1710), showing, on the right, the attacking trenches and batteries of the Duke of Marlborough’s forces. The ‘Aproches’ zig-zagged between the successively advanced ‘parallels’ in a way that exactly prefigured First World War communication trenches (approaches or avenues). The batteries fired at Vauban’s fortifications until a breach was made, and when this was deemed ‘practicable’ the infantry assault was launched.

Historical Overview

Trenches and field fortifications were not a new concept and have existed in various forms since pre-history. A principal feature of warfare in the medieval and renaissance periods (Leonardo da Vinci was a military engineer), they had assumed a new importance with the invention of gunpowder and firearms, and by the 17th century sieges had become intricate and scientific affairs with a vast trench vocabulary, much of which survived into the 20th century. Readers of Lawrence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (1757) will recognise, in Uncle Toby’s development of sieges in miniature on his bowling green, the parallels (in more than one sense) between early 18th-century siege warfare and the Western Front in 1914–18, including the use of mortars. The Crimean and American Civil Wars of the 19th-century saw the widespread use of trenches and breastworks, while the Russo–Japanese War of 1904–5 and Balkan Wars of 1912–13 drove home the message that trench warfare was likely to be a significant feature of early 20th-century conflict, at least at certain stages of operations.

Permanent fortifications had always been named for identification, and earlier wars had seen names given to temporary field works for the same reason, for example the La Bassée Lines and Louis XIV’s Ne Plus Ultra Lines of Marlborough’s time, and Wellington’s Lines of Torres Vedras in the Peninsula. In the Crimean War, the Great Redoubt and Lesser Redoubt crowned the heights of the Alma, the Sandbag Redoubt appeared, and the prolonged siege of Sebastopol was executed according to classic siege-war principles. Many features and works here were named accordingly: the Great Redan, Little Redan and Malakoff redoubts defending Sebastopol, the Mamelon, McKenzie’s Heights, Frenchman’s Hill, Greenhill, Tryon’s Trench, the Cochorn Battery, Lancaster Right and Left Batteries, the Allied Picquet House, Left, Right and New Boyaux (approaches or communication trenches), Victoria Redoubt and the 1st to 5th Parallels, from the last of which the Allied assault was launched. Several of these names were to reappear on the Western Front in 1914–18.

The practice of naming defensive lines continued after the Crimean and American Civil Wars, with the Bulair Lines defending the Gallipoli Peninsula and the Chataldja Lines defending Constantinople in the Balkan Wars, and so forth. Most of the defence lines took their names from the local topography. On the Eastern Front in 1914, the Germans held back the invading Russians on the Angerapp Line in East Prussia. In the west, 1914 saw many permanent fortifications facing the German invader, and in key defensive zones such as Serré de Rivière’s Verdun–Nancy–Belfort fortress belt defending France’s eastern frontier there were many named forts, ouvrages, batteries and so forth. When these were augmented by temporary earthworks, it was natural that they should be similarly named. Thus another reason for trench naming was historical precedent – it had always been done, and had been picked up by regular soldiers and others from reading regimental and campaign histories.

1914 – The Start of Trench Warfare

The infantry soldiers of 1914 were trained in the first instance to dig individual scrapes and rifle pits with their ‘grubbers’ or entrenching tools, which they all carried, and with which they quickly dug in at Mons and Le Cateau. If no forward movement was possible or rearward movement intended, they were trained to link these up into fire trenches as soon as possible. Sections of fire-trench were then linked laterally to provide communication between sections, platoons, companies and then battalions, and also forward and backward to provide communication between firing line, supports and reserves, and with headquarters. All this was provided for in pre-war training manuals.

This pattern had developed on the Aisne in September 1914 within two weeks of movement coming to a halt, with Field Companies of the Royal Engineers helping to survey and construct defences. In open country, modern weapons made it quite impossible to move in daylight without such communications, and even at night heavy casualties could be expected in moonlight, or when the enemy were equipped with flares. In any case, even if illumination was lacking, the ground would be swept by rifles and machine guns firing on fixed lines. Brigadier General Hunter-Weston was proud of the trenches constructed by his 11th Brigade, and exhorted his battalion commanders to take the education of their officers in trench construction very seriously. On 30 September 1914 his brigade major sent the following message to each battalion (Hants, Rifle Brigade, Somersets, East Lancs):

Brig-Gen is desirous that all the Officers of the battalions should profit by the experience of entrenching under active service conditions which is now afforded by our sections of defence. He is of opinion that most of the work [which] is now executed is admirable. He directs therefore that commanding officers will go round the whole section of defence with half the officers of their battalions today and with the other half tomorrow pointing out for instruction purposes the good and bad points of the various works.1

The troops again dug in during the encounter battles of La Bassée and First Ypres in October and November 1914, and at the end of these battles the trench system again solidified, as it had on the Aisne. Trenches, or in waterlogged terrain breastworks (as in parts of the Ypres Salient and long stretches of the line southwards to Festubert and Givenchy) were essential for survival, and some form of primitive ‘splinter-proofs’ or dugouts had to be provided for protection from fire and the weather. In the winter of 1914–15, the infantry and engineers watched helplessly as trenches filled with water and sandbag breastworks spread and sank into the slime. The most that could be done in several low-lying parts of the front – notably the Lys Valley and parts of the Ypres Salient – was to construct short lengths of revetted breastwork (‘grouse butts’ or ‘islands’), reached only by night by an overland route, which could be held by outlying pickets, most men of the front battalions remaining in ‘keeps’, ruins and villages behind the front line. Where possible, wire was strung out in front of these meagre defences to improve their security. Grim ground conditions were nothing new in warfare, or in Flanders. Uncle Toby, in Tristram Shandy, declared that ‘Our armies swore terribly in Flanders’.

British and German front breastworks in the low-lying Richebourg sector facing the Aubers Ridge, May 1915. The British front breastwork is two-thirds of the way up the photo, and beyond that lies no man’s land and the German front breastwork. Further on again rises the Aubers Ridge.

Trenches systems did not grow at random. Vital to their planning and siting were the experts in field works – the Divisional Royal Engineers, and the all-important ‘defence scheme’ for each sector that detailed the units and sub-units responsible for holding each trench or feature, their dispositions and ‘stand-to’ positions, and their deployment to meet an expected attack. The scheme included support and reserve positions, and routes to be used to reinforce and counter-attack. Over an extended period of time, the relationship between a defence scheme and trench system was symbiotic; the original defence scheme determined the trace of the trenches on the ground (though this was also partly inherited from the first scrapes and diggings of the initial encounter battles), and where brigadiers, divisional, corps and army commanders felt that there needed to be changes or developments these took concrete form in the shape of new trenches, dugouts and tunnels, machine gun and mortar emplacements, battery positions, etc. The pattern of trenches might also be changed in response to geological and terrain conditions – an old, waterlogged line would be abandoned and replaced by a new line on higher ground, or an exposed position on a forward slope would be replaced by a protected one (with a good field of fire) on a reverse slope, leaving only observation posts forward, with saps running back to the new line.

1915 – Trench Systems...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 21.8.2017 |

|---|---|

| Vorwort | Alan Sillitoe |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Sprachwissenschaft | |

| Schlagworte | Analysis • battles • british trenches • Crazy Redoubt • Cultural Life • Cyanide Trench • Doleful Post • Extended • First World War • French trenches, german trenches, trench-naming practices, trench warfare, cultural life, battles, original trench maps, Lovers Lane, Idiot Corner, Cyanide Trench, Crazy Redoubt, Doleful Post, Furies Trench, Peril Avenue, Lunatic Sap, Gangrene Alley, trench names of the western front 1914-1918 • Furies Trench • Gangrene Alley • gazetteer • german trenches • Idiot Corner • landscape|French trenches • Lovers Lane • Lunatic Sap • map references • Maps • original trench maps • Peril Avenue • Revised • The Great War • The Trenches • Tommy • Trench • trench, front line, tommy, trenches, western front trenches, the trenches, trench names of the western front, Lovers Lane, Idiot Corner, Cyanide Trench, Crazy Redoubt, Doleful Post, Furies Trench, Peril Avenue, Lunatic Sap, Gangrene Alley, first world war, great war, the great war, world war i, • trench names • trench names of the western front • trench names of the western front 1914-1918 • trench naming • trench-naming practices • trench warfare • Updated • western front trenches • World War 1 • world war 1, world war one, ww1, wwi, • World War I • World War One • WW1 • wwi • wwi, ww1, world war one, world war I, world war 1, first world war, the great war, trench, the trenches, trench names, tommy, western front trenches, trench names of the western front, updated, revised, gazetteer, extended, map references, maps, analysis, trench naming, british trenches, landscape |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7509-8490-2 / 0750984902 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7509-8490-4 / 9780750984904 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 53,3 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich