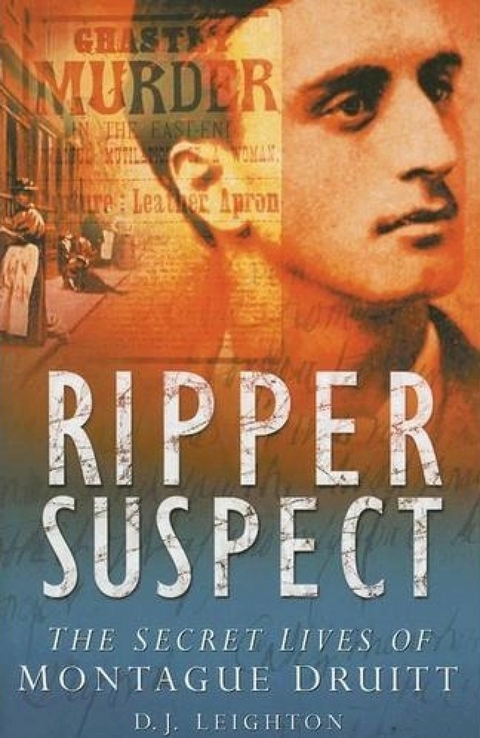

Ripper Suspect (eBook)

224 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7509-8134-7 (ISBN)

ONE

The Scene is Set

In the autumn of 1888 in the Whitechapel area of east London five appalling murders took place. All the victims were prostitutes; four of them were mutilated and parts of their bodies removed. The nature of the crimes led the police to believe that they were the work of one person. Then taunting letters began to arrive, signed by someone calling himself ‘Jack the Ripper’. This was a nasty but accurate description of the murderer’s work. The killings became known as the Jack the Ripper murders, and the obloquy has helped to ensure that the case has remained high in the general public’s awareness to this day.

Since the mid-1990s, forty new books on the subject have been published. This is higher than for any other true-life crime. Patricia Cornwell’s Portrait of a Killer demonstrates the huge interest that continues to exist in the subject. The paperback edition was an international bestseller, topped the Sunday Times lists for six weeks and sold over 150,000 copies between September 2003 and the end of that year. Even today the Ripper’s frightening spectre retains its power. In May 2005 Michael Winner, writing his restaurant column also in the Sunday Times, recorded that his friend Paola Lombard disliked the small Italian village of Apricale. She thought the narrow, cobbled streets ‘were spooky’. ‘I expect to meet Jack the Ripper any moment,’ she said. Some writers and historians have listed as many as twelve victims of the Ripper, but five is the generally accepted number.

This, briefly, is a summary of those murders.

The first woman to die was Mary Ann Nichols, who was found on Friday, 31 August, at about 3.30 a.m. near a Kearley and Tonge warehouse in Bucks Row (now Durward Street), her body slashed and mutilated. Nichols had been born in 1845 in east London and by the time she was 19 she was married to William Nichols, a printer. This relationship produced five children but ended in 1880, partly because of her heavy drinking. For the rest of her life she lived mostly in workhouses, slept rough or rented the cheapest room in the worst areas of the East End. Earlier that Friday night she had boasted to a friend about her successful earnings that evening. She was drunk. Her body was identified a few hours later by her husband and the same family friend, Emily Holland. The police surgeon who carried out the post-mortem was Dr Ralph Llewellyn and the coroner was Wynne Baxter. At first Llewellyn believed the murderer was left-handed but later he became less sure. He was, however, firm in his opinion that the killer ‘must have some anatomical knowledge’. He commented, ‘I have never seen so horrible a case.’

The second victim was 47-year-old Annie Chapman, who died at about 5.30 a.m. on Saturday, 8 September, in Hanbury Street, which leads into Commercial Street. At one time she had been married, with three children, to a coachman, John Chapman, in Windsor, but they had separated in 1884 and she had moved to Whitechapel, where she sold flowers, did some sewing and worked the streets at nights. Between times she drank in local pubs. On the night of her murder she had been plying her trade to make money for her room. This time the police surgeon handling the post-mortem was Dr George Bagster Phillips. It was his view that there had been an attempt at decapitation, but in any event her body had been horribly cut up, and it was clear to Dr Phillips that the assailant had medical knowledge of anatomy and pathology. The coroner as for the first victim was Wynne Baxter and he agreed with these findings. He also drew attention to the removal of body parts.

On Sunday, 30 September, two Ripper murders took place and these became known as the ‘Double Event’. The first to die was Elizabeth Stride, who was killed at about 1.00 a.m. in Dutfield’s Yard, near the Commercial Road. Stride was born in Sweden in 1843, and became involved in prostitution at the age of 21. In 1866 she moved to London, married a John Stride three years later, and went to live in Clerkenwell. In 1878 the pleasure steamer Princess Alice sank in the River Thames and 527 lives were lost. Stride invented the story that her husband and children were among the victims, but in fact John Stride died in the Poplar Union Workhouse in 1884, three years after the marriage had ended. Elizabeth Stride now reverted to her old profession, and in the hours before her death had spent the time drinking and soliciting. Again Dr Phillips held the post-mortem and Wynne Baxter was the coroner. Death was by a cut to the throat, and Baxter believed the murderer ‘knew where to cut’. The absence of mutilation suggested to the coroner that the killer had been disturbed, but the death is still attributed to the Ripper.

On the same night about half an hour after the murder of Elizabeth Stride another woman was killed a few hundred yards away in Mitre Square. The Kearley and Tonge head office occupied two sides of the Square, so it was the second time a victim had been found near Kearley and Tonge premises. Her name was Catherine Eddowes, aged 46, and she had been brought up as an orphan in a workhouse. She settled in Whitechapel with a soldier Thomas Conway with whom she had three children, but the relationship ended in 1880 partly because of Eddowes’s alcoholism. She soon moved in with John Kelly, a labourer, and became variously known as Eddowes, Conway and Kelly. Although extremely poor, she may have been a casual, rather than a career, prostitute, and the two scraped a living doing agricultural work. The time prior to the murder is well documented as she had been in police custody until 1.00 a.m. sobering up from a drinking binge. Within an hour of her release she was dead; her throat had been cut, her body slashed and parts removed. Dr Frederick Gordon Brown carried out the post-mortem and noted: ‘I believe the perpetrator of the act must have had considerable knowledge of the position of the organs. It would have needed great knowledge.’ Eddowes’s death had all the hallmarks of an authentic Ripper murder. There is, however, a possibility that the murder was a mistake, as she may not have been a regular prostitute and could have been confused with the fifth victim.

The last of the five women to be killed was Mary Jane Kelly in the early hours of Friday, 9 November, in Miller’s Court, near Commercial Street. Her background and life were desperate. Born in Limerick in 1862, she moved to Wales and married a coal miner called Jonathan Davies when she was 16. Within months Davies was killed in a pit accident, and Kelly was introduced to prostitution in Cardiff by her aunt. In 1884 she moved to London and worked partly in a gentlemen’s gay club and partly in a West End brothel. Eventually she moved to the East End, an even more degrading environment, where she continued to ply her trade. She was last seen at about 1.00 a.m. on the Friday morning the worse for drink. Her body was found cut up almost beyond identification, and of all the murders this was the most gruesome. Dr Phillips again did the post-mortem and Mr Roderick MacDonald was the coroner.

These then are the five murders. The only motives can have been a gruesome sexual gratification, a twisted mission against prostitutes or an urge to silence certain people. All were too poor to be robbed. No one was ever charged or convicted, and, although dozens of men were interviewed, the investigation progressed no further.

There was no shortage of candidates, even claimants. The Lewisham Gazette of 7 December 1888 reported under the headline ‘Jack the Ripper in a Fish Shop’ that a John Weidon of Francis Street, Woolwich, had entered a fish shop owned by Mr and Mrs Seagain in New Cross Road. On being refused credit, Weidon began to smash up bottles and plates and threatened, ‘I am Jack the Ripper and will do for you.’ He was fined 10s (50p) with 2s costs, or seven days in prison.

Six years later the Chief Constable of the Metropolitan area, Sir Melville Macnaghten, named Montague Druitt as the murderer, but by then Druitt was dead. Nevertheless, for the last 100 years Druitt’s name has been inextricably linked with that of Jack the Ripper. This book tells the life of Montague Druitt, and the circumstances that surrounded him. It examines the validity of Macnaghten’s claim in the light of this evidence.

At the time of the murders, the East End of London had a population approaching a million, of which some 80,000 lived in the Whitechapel area. The East End as a whole was an area of abject poverty and dreadful living conditions. Charles Dickens had placed his characters Fagin and Bill Sikes in Whitechapel, the seediest part of London he knew. To see starving and dying people on the streets was not uncommon. The small squalid houses were hopelessly overcrowded, and often there was a room occupancy of six or more people. There was no large-scale industry such as mills or other manufacturing to sustain the people who would have gained such employment in the northern cities. There was some work for men in the London docks, but this was fiercely controlled so that only those perceived as being English could participate. The railways, too, provided limited work, but mostly men relied on occasional building jobs, street trading or hard manual labour, working long hours for £1 per week. Much of the population was drifting and rootless. Jewish and Eastern European enclaves were formed, and itinerant sailors up from the docks came and went. Nor did it help that gang warfare had arrived early in the nineteenth century, and by the 1880s groups of thugs such as the Old Nichol Gang, the Blind Beggar Mob, the Green Gate Gang and the Hoxton Mob were roaming the streets. Some gangs...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 23.9.2016 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Krimi / Thriller / Horror ► Krimi / Thriller | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Recht / Steuern ► Strafrecht ► Kriminologie | |

| Sozialwissenschaften | |

| Schlagworte | aristocracy • aristocratic • Cambridge Apostles • criminal • homosexual • Jack the Ripper • jack the ripper, jack the ripper suspect, who was jack the ripper, ripperology, ripperologists, whitechapel, victorian era, victorian, victorian crime, Montague Druitt, criminal, aristocratic, aristocracy, homosexual, London, Sir Melville Macnaughten, real crime, true crime, crime • jack the ripper, jack the ripper suspect, who was jack the ripper, ripperology, ripperologists, whitechapel, victorian era, victorian, victorian crime, Montague Druitt, criminal, aristocratic, aristocracy, homosexual, London, Sir Melville Macnaughten, real crime, true crime, The Secret Lives of Montague Druitt, cambridge apostles, sir arthur conan doyle, virginia woolf, prince kumar ranjitsinhji, victorian underworld • jack the ripper suspect • London • Montague Druitt • prince kumar ranjitsinhji • Real Crime • Ripperologists • ripperology • Sir Arthur Conan Doyle • Sir Melville Macnaughten • The Secret Lives of Montague Druitt • True Crime • Victorian • victorian crime • Victorian Era • victorian underworld • Virginia Woolf • Whitechapel • Who Was Jack the Ripper |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7509-8134-2 / 0750981342 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7509-8134-7 / 9780750981347 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 6,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich