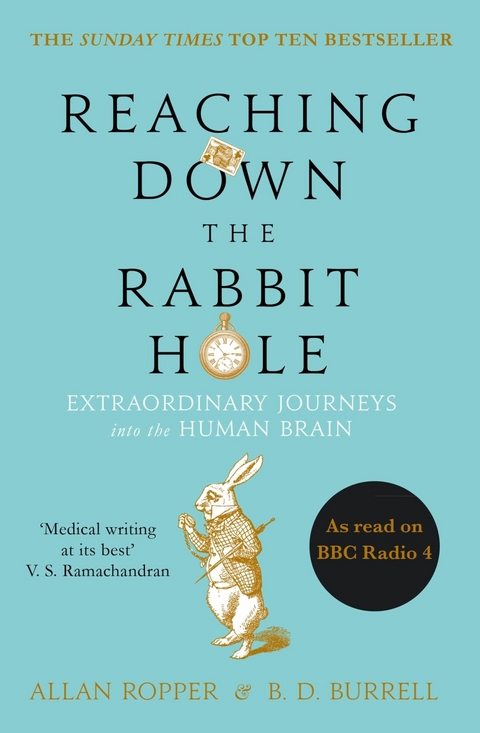

Reaching Down the Rabbit Hole (eBook)

272 Seiten

Atlantic Books (Verlag)

9781782395492 (ISBN)

One of the world's leading neurologists reveals the extraordinary stories behind some of the brain disorders that he and his staff at the Harvard Medical School endeavour to treat.

What is it like to try to heal the body when the mind is under attack? In this gripping and illuminating book, Dr Allan Ropper reveals the extraordinary stories behind some of the life-altering afflictions that he and his staff are confronted with at the Neurology Unit of Harvard's Brigham and Women's Hospital.

Like Alice in Wonderland, Dr Ropper inhabits a place where absurdities abound: a sportsman who starts spouting gibberish; an undergraduate who suddenly becomes psychotic; a mother who has to decide whether a life locked inside her own head is worth living. How does one begin to treat such cases, to counsel people whose lives may be changed forever? Dr Ropper answers these questions by taking the reader into a world where lives and minds hang in the balance.

Dr Allan H. Ropper is a Professor at Harvard Medical School and the Raymond D. Adams Master Clinician at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston. He is credited with founding the field of neurological intensive care and counts Michael J. Fox among his patients. B. D. Burrell is the author of Postcards from the Brain Museum. He has appeared on the Today Show, Booknotes, and NPR's Morning Edition. He divides his time between writing and statistical research with neuroscientific applications.

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 2.10.2014 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Psychologie ► Klinische Psychologie | |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Allgemeines / Lexika | |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Medizinische Fachgebiete ► Neurologie | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Humanbiologie | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Zoologie | |

| Technik | |

| Schlagworte | Atul Gawande • Being Mortal • brain • do no harm • Henry Marsh • Neurology • Neuroscience • Oliver Sacks • Paul Kalanithi • siddhartha mukherjee • The Emperor of all maladies • The Gene • the man who mistook his wife for a hat • When Breath Becomes Air |

| ISBN-13 | 9781782395492 / 9781782395492 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich