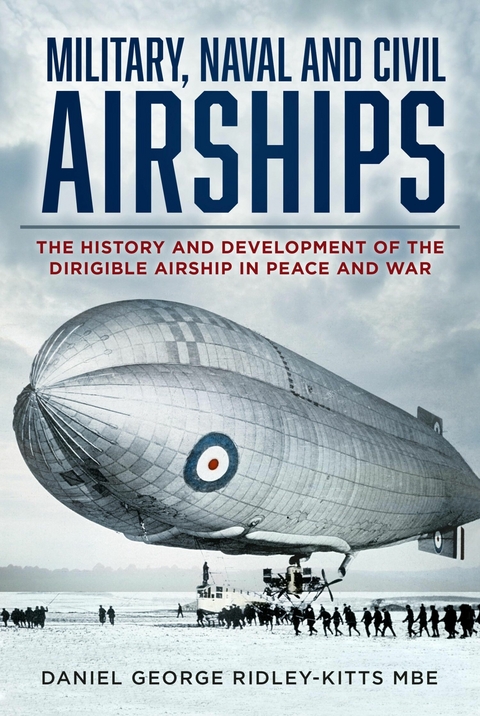

Military, Naval and Civil Airships (eBook)

300 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7524-9037-3 (ISBN)

DANIEL G RIDLEY-KITTS MBE worked in the aircraft industry after leaving school and served in the RAF as a national serviceman on a fighter squadron in Germany. He was made MBE in the 1994 New Year's Honours List for 'Services to the Oil Industry'.

INTRODUCTION

The Conquest of the Air

The dream of human flight is a recurring image in the history of mankind, with man’s earliest attempts to fly based, not unnaturally, on an imitation of bird flight. The history of manned flight from Icarus onward is littered with mad tower jumpers launching themselves into the void, with flapping wings strapped to their backs. Later came the more reasoned and considered works of Leonardo da Vinci, and other early pioneers, who struggled to understand the secrets of flying with all their essays based on the principle of heavier-than-air flight.

There is no obvious parallel in nature that corresponds to the lighter-than-air principle that airships rely on to ‘float’ in the air, but the monk and natural philosopher Roger Bacon (1214–94) speculated that the atmosphere above the earth possessed an upper surface on which ‘an aerial vessel could be made to float on this sea of air’. In his work Secrets of Art and Nature, written in 1250, he describes such a craft as being: ‘a large hollow globe fashioned from copper, wrought very thin in order to save weight, and to be filled with “Ethereal air” or “Liquid fire”, then to be launched from an elevated point into the atmosphere, where it will float as a boat on water.’

Francisco de Mendoza (d. 1626) also considered the employment of what he termed ‘elementary fire’ to maintain such a vessel in the air, where it could be propelled by oars. Better known are the writings of Francesco de Lana (1631–87), who proposed a ‘flying boat’ that would float in the atmosphere by virtue of four large copper globes from which the air had been evacuated; the resulting displacement of air being sufficient to provide the necessary lift.

De Lana had in fact conducted experiments to determine the weight of air, the results of which – despite the primitive apparatus at his disposal – were very close to the modern accepted measurements. Unfortunately, the scheme was completely impractical, as de Lana had failed to appreciate that the atmospheric pressure acting on the evacuated globes, which he thought would help to consolidate the spheres, would in fact crush them flat. De Lana did, however, foresee the use of flying machines in warfare, with the bombing of fortresses and ships at sea by the dropping of ‘fire balls’ and the rapid transportation of troops, together with describing their employment for commerce.

The invention of the hot air balloon is generally ascribed to the Montgolfier brothers in 1783, with the first manned flight made by Pilâtre de Rozier on 15 October of that year, in Paris. This event was followed, in December 1783, by the first manned ascent of a hydrogen balloon under the direction of the physicist J.A.C. Charles, which was to become the more practical and convenient form of craft for the purpose of aerial navigation. Indeed, the superiority of the hydrogen balloon was quickly established over its hot air competitor in terms of convenience of operation and its ability to conduct flights of greater duration.

The rapid pace of the development of the hot air and the hydrogen balloon following the Montgolfiers’ first flight was extraordinary: within just over a year Blanchard and Jeffries had completed the first crossing of the English Channel, and ascents were being made in London and other European capitals during this period.

Throughout the nineteenth century, as intrepid balloonists became ever more familiar with the ocean of the air, undertaking long voyages and making high-altitude ascents to study the composition of the upper atmosphere, they were still at the mercy of the winds that determined the direction of travel. The question of effective control, together with a method of propulsion, exercised the mind of the early aeronauts, and various wildly impractical schemes were suggested, including the use of oars and sails, or even being towed by trained birds.

The first scientifically based solution for controlled dirigible flight was put forward only days after the first ascent of the hydrogen balloon in 1783, when the brilliant French army officer and savant, Jean Baptiste Meusnier, proposed the design of an elongated ellipsoidal balloon. Driven through the air by three propellers and operated by manual power, this was the first application of the airscrew in aviation. Although it was not built, Meusnier’s design incorporated almost all the features to be found in modern airships.

In 1852 Henri Giffard built a steam-powered dirigible with which he was able to achieve a degree of control, although he was unable to navigate a circular course and return to his starting place. Twenty years on, in 1872, Austrian Paul Haenlein flew an airship propelled by a Lenoir gas engine, the fuel for which was supplied from the airship’s envelope, again with some success.

Later, in 1883, the famed balloonists the Tissander brothers applied electric power in the search for an effective and powerful prime mover, although their results were of limited success. This effort was quickly followed, in 1884, by the more successful experiments under the direction of Renard and Krebs of the French army aeronautical establishment at Chalais Meudon, again employing electrical power with the airship La France. In a series of trials the airship demonstrated controlled flight, achieved a speed of 14mph and made several flights over Paris. However, the disproportionate weight of the electric batteries it carried, and its limited range and carrying capacity, militated against further development.

Throughout the later years of the nineteenth century ballooning became a popular sport of the wealthy upper classes, particularly in Europe where many flights of long duration were accomplished, flights from England to Russia or other parts of the Continent being not uncommon. It was not until the development of the internal combustion engine in the late 1890s, however, that the airship finally became a practical craft.

One such wealthy aeronaut was a young Brazilian heir to a coffee fortune, Alberto Santos-Dumont. In 1898, tiring of the thrills of ballooning, Santos-Dumont turned his attention to the building of a series of small and, as it turned out, highly efficient pressure airships propelled by petrol engines. His highly publicised aerial activities over Paris – including winning the prestigious Deutsch de la Meurthe prize in November 1901 for the first flight from St Cloud, around the Eiffel Tower and returning to the starting point – did much to stimulate interest in the future development of the airship.

Concurrently, Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin was conducting experimental flights with his giant rigid-framed dirigible on Lake Constance in southern Germany. Whilst the French, led by the Lebaudy brothers, were developing another form of airship structure: the semi-rigid type.

From 1900 to 1914 several hundred airships of all designs were produced in Europe and the United States; some for sporting purposes and some for commercial passenger carrying. However, in the period in question – one of rising international tension – many airships were designed with a military purpose in mind, as the airship was seen to be a potential weapon of war.

In Germany Count Zeppelin, who had conceived his airship for war purposes in a patriotic desire to provide an air fleet to protect the nation, was frustrated by an initial lack of interest from the military authorities. In May 1909, with no military contract in the offing, Alfred Colsman, the general manager of the fledgling Zeppelin concern, suggested that a separate company should be formed to operate a passenger-carrying service. This would initially operate pleasure flights of short duration, and later the company would initiate regular scheduled services between major German cities.

The count was not himself in favour of such commercial activities, but under Colsman’s persuasive and reasoned arguments he finally agreed to the scheme, which would allow for the further development and perfection of his invention. The company, Deutsche Luftschiffahrts-Aktiengesellschaft (DELAG), was thus founded in November 1909 with a capital of 3 million Marks. They ordered their first airship, Deutschland, while Colsman negotiated with the burgomasters of large towns throughout Germany to provide ‘aerial harbours’ to house the envisaged fleet of airships.

The proposed regular service between cities failed to materialise, but DELAG did operate seven passenger airships between June 1910 and July 1914, carrying 34,000 passengers and crew on 1,500 flights without any fatalities – although three airships were destroyed in accidents. The success of these early commercial undertakings encouraged the military and naval authorities to develop the airship for war purposes, with the army operating eight Zeppelin and a score of other airships in service at the outbreak of the war in 1914.

The parallel development of the heavier-than-air flying machine during this period created two groups of adherents: those who favoured the airship were convinced that, due to its greater lifting capacity, it would ultimately carry the main aerial commerce of the world; whilst the visionary pioneers in their frail ‘flying machines’ were equally certain that the success of air transport lay with the aeroplane.

At the start of the Great War the Zeppelin was regarded as a potent weapon, which, thanks to popular writers of the time, was imbued with tremendous powers of destruction and initially appeared to be immune from attack by the primitive aeroplanes. As the war progressed the aeroplane gained the upper hand, however. By the war’s end, with the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.3.2012 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Luftfahrt / Raumfahrt | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Psychologie | |

| Technik | |

| Schlagworte | aeronauts • Aircraft • Airship • air travel • aviation history • count zeppelin • Dirigibles • The History and Development of the Dirigible Airship in Peace & War • The History and Development of the Dirigible Airship in Peace and War • The History and Development of the Dirigible Airship in Peace and War, The History and Development of the Dirigible Airship in Peace & War, dirigibles, airship, aircraft, aeronauts, count zeppelin, air travel, aviation history |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7524-9037-0 / 0752490370 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7524-9037-3 / 9780752490373 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 30,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich