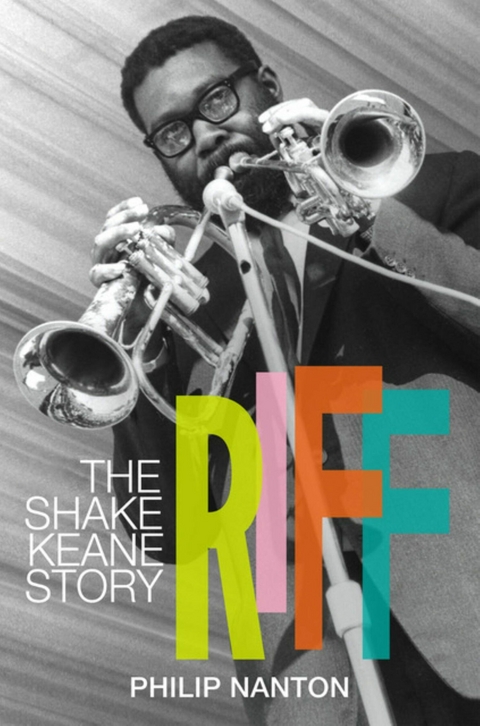

Riff (eBook)

256 Seiten

Papillote Press (Verlag)

978-1-8380415-1-9 (ISBN)

Philip Nanton is a writer, poet and performer Born in St Vincent, he now lives in Barbados. He is an honorary Research Associate at the University of Birmingham and occasional lecturer at the Cave Hill campus of the University of the West Indies, Barbados. He has made radio documentaries on Caribbean literature and culture for the BBC. His books, Island Voices for St. Christopher and the Barracudas (2014) and Canouan Suite and Other Pieces (2016), mix poetry and prose, and were both published by Papillote Press. His latest book, Frontiers of the Caribbean (2017) was published by Manchester University Press.

Philip Nanton is a writer, poet and performer Born in St Vincent, he now lives in Barbados. He is an honorary Research Associate at the University of Birmingham and occasional lecturer at the Cave Hill campus of the University of the West Indies, Barbados. He has made radio documentaries on Caribbean literature and culture for the BBC. His books, Island Voices for St. Christopher and the Barracudas (2014) and Canouan Suite and Other Pieces (2016), mix poetry and prose, and were both published by Papillote Press. His latest book, Frontiers of the Caribbean (2017) was published by Manchester University Press.

RIFF

2/‘BLESSED LITTLE HOME-HOME ISLAND’

We were children

when corked hats and plumed feathers

were among the heights of fashion

when you walked to church to hear a preacher’s sermon

and teaching was a serious profession

clinking the keys to our future.1

‘Shake’ Keane was born Ellsworth McGranahan Keane on 30 May 1927 in Kingstown. He was the third son and fifth of seven children of Charles E Keane (1869-1941) and Dorcas Maude née Edwards (nd - 1963) widely known as ‘Jessie’. The total number of children that Charles fathered is uncertain — Shake claimed ‘many’ half siblings. He said that his father had been married twice before his marriage to Jessie. The registry office lists only six children from the marriage of Charles and Dorcas. His older siblings were Hadassah Magdalin Roxann, Theodore Vanragin, Edna Elaine, McIntyne Wilberforce, then there was Shake, Donny (unlisted) and Darnell Mendelssola. Certainly, Charles and Jessie were attracted to grand names for their offspring.

The family was culturally rich but economically poor. His father was a self-educated man who managed money badly and held a variety of jobs. Two were significant: he worked at different times as an estate overseer and as a corporal in the Royal St Vincent Police.2 In the countryside, where Charles was based before moving to Kingstown, both jobs held authority and power. According to Shake, these positions of local status also accounted for Charles’s substantial but unquantified extended family.

Music as an interest came about by chance while Charles was living and working in the countryside. The three prominent positions in the island’s rural villages at this time were the police corporal, the school principal and the estate overseer. With few diversions and no electricity, these three authority figures would get together most evenings. As Shake told it, the Principal, a Mr Drayton, an able musician from Barbados, offered to teach Charles the rudiments of music. Charles had an aptitude and soon could read music, hold a note and play the trumpet. And so music was born as an occupation in the Keane household. It is not known what year Charles moved to Kingstown, but both the marriage of Charles and Dorcas as well as the birth of their first child were officially registered in Kingstown in 1916.

It is possible that in recognition of the family’s religious affiliations as Methodists and love of music, Charles and Dorcas gave their third son the middle name of McGranahan after James McGranahan, the nineteenth-century American composer of hymns, whom Charles admired. The first name, Ellsworth, popular in the first decade of the twentieth century, is derived from the Old English name Ellias and evokes nobility. With names such as ‘Ellsworth’ and ‘McGranahan’, it is perhaps not surprising that he was more often known in his early years by his nicknames: firstly, ‘Muz’, possibly short for ‘music’ given his public performances at an early age, and later ‘Shake’. He answered to ‘Muz’ Keane throughout his early school and teaching days and even when signing letters to friends. But over time, ‘Shake’ was the name that stuck. There are at least two versions of its origins. According to one story, it is a diminutive of ‘Shakespeare’, given to him by school friends and musicians in honour of his love of literature. Another story links it to his fondness for a particular Duke Ellington tune of the 1940s in which the trumpet features prominently — ‘Chocolate Shake’. Whichever version is true, the nickname alludes to his three great passions: music, English literature and the poetry of the Caribbean.

Early twentieth-century Kingstown was a mixture of poverty and aspiration. Unlike modern Kingstown with its concrete and glass business structures, the town centre then comprised both residences and places of work, often in the same building. In the 1930s only a few public streets had electric lights, and at night homes were lit by candles and oil lamps. The core of the capital was its three main streets. Bay Street and Back Street sandwiched Middle Street, in the lower section of which — called Lower Middle Street — the Keane family lived. Homes and businesses for the most part were small clapboard houses comprising ground and first floor. The family home was located in a lively artisanal area with open gutters running on both sides of the street. There were two blacksmiths nearby, as well as a small printery. From his upstairs bedroom window Shake could see into a nearby bakery, where the sweat poured off the backs of bakers kneading dough for their ovens. In the neighbourhood could be found two brass bands — the Keane family band and Cyril McIntosh’s Brass Band — as well as Melody Makers Steel Band, and further up the street Syncopators Steel Band.3 Black families, like the Keanes, could be classified as artisans aspiring to middle-class status, with homes slightly removed from the town’s administrative centre.

Nearer the centre of the town could be found wealthier middle-class families. Their stone-walled houses were primarily residential, characterised by cooling arches that supported overhead balconies. White planters and business people, who often intermarried, represented the island’s elite and lived in those houses close to the town centre until the mid-twentieth-century fashion of living outside the capital took hold.

Despite these contrasts, the St Vincent of Shake’s birth was a small outpost, often referred to in colonial parlance as a ‘minor colony’. In 1927 the island had 49,751 inhabitants.4 It was run by an administrator from Britain and three elected and nominated local members of the island’s Legislative Council. The electoral roll was tiny and based on land ownership, and nominated members were white planters who invariably sided with the colonial authorities. In his annual report for 1927, the Administrator, Robert Walter, expressed his pride that the island’s finances were stable. The economy was essentially agricultural and his main concern was that someone should establish a hotel to kick-start a tourist industry. His pitch for tourism in the official yearbook was based on the charm of St Vincent’s volcanic mountains and the character of its people. ‘The people of St Vincent,’ he claimed, ‘are extremely warm-hearted, law-abiding, simple and in many ways most attractive and lovable.’5 In fact, the social reality and political undercurrents were considerably different from this official view of island tranquillity.

In 1935, when Shake was eight, Kingstown erupted in a riot — the immediate cause of which was a protest against the insensitivity of the colonial administration in imposing a local tax on household matches. Afflicted by poverty and lack of work, ordinary people feared that a tax on such a basic commodity would worsen their already difficult plight. In October that year, attempts by the region’s Governor, Selwyn MacGregor Grier, to deny the negative impact of the tax, as he tried to negotiate with a restless crowd gathered in front of the island’s Court House, singularly failed. Fearing that the Governor, who was in charge of the Windward Islands, including St Vincent, would depart the island for his residence in Grenada before the issue was settled, voices were raised, business houses wrecked and policemen were beaten and trampled. In turn, the police fired their guns above and into the crowd. Rioting led to days of looting of shops in Kingstown and Georgetown as well as threats to white planters, and the call for a British naval gunboat to help restore order. The reality that underlay the riot was severe long-term poverty and unemployment for the island’s poorer urban and rural black working class, who did not have the option of obtaining land to secure a livelihood.

The rioters probably had less to lose than the aspirational and relatively respectable black urban strata in which the Keane family were located. As a one-time police officer, Charles’s sympathies are unlikely to have been on the side of the protesters. The family were regular churchgoers and Charles often organised singing evenings in neighbours’ homes. These features of the Keane family suggest that Charles’s aims for the family were geared more towards self-improvement than political action.

However, not all family members were quiescent. From an early age Shake expressed through his music a commitment to his island’s development. He and his brother Don played at the rallies of the Working Men’s Co-operative Association (WMCA), to enliven the crowd prior to speeches and hustings for the Legislative Council elections. The WMCA set up co-operative groups and helped informally in labour negotiations. Popular with grass-roots voters, the WMCA won four of the five seats in the 1937 election for membership of the island’s Legislative Council. Also, from Shake’s early published writing it is clear that he was a committed regionalist who looked forward to federation. This view was modified in later life when he argued the benefits of ‘gradual arrangements to come together.’6

Charles taught each of his children to read music, to sing and play a musical instrument.7 With his police-force background, he was a strict...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 21.12.2020 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Newcastle upon Tyne |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Musik ► Jazz / Blues | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Esoterik / Spiritualität | |

| Schlagworte | Caribbean • Jazz • London • Poetry |

| ISBN-10 | 1-8380415-1-6 / 1838041516 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-8380415-1-9 / 9781838041519 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,0 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich