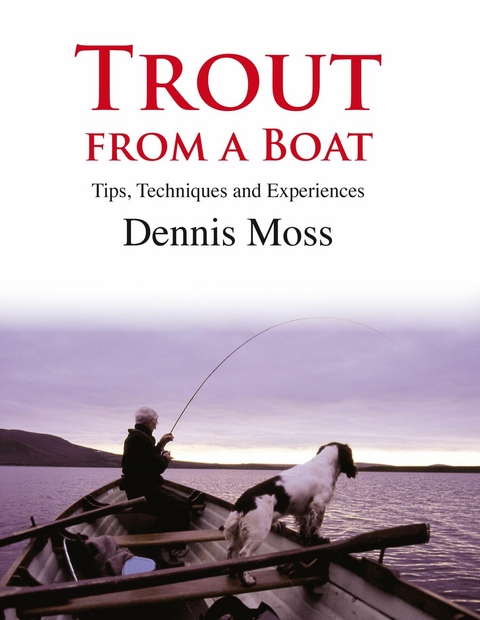

Trout from a Boat (eBook)

160 Seiten

Merlin Unwin Books (Verlag)

978-1-910723-87-6 (ISBN)

Dennis Moss is a regular contributor to Trout & Salmon magazine. He spent his working career in the fishing tackle trade; his spare time mastering boat fishing from England's classic stillwater reservoirs, to the Outer Hebrides and Irish loughs. He now lives in retirement on Lough Corrib.

I enjoy bank fishing, particularly on the larger fisheries where one is free to roam in search of fish. Working down a shoreline, systematically covering new water, can be a very satisfying and absorbing way to fish. Time becomes immaterial as I slip into an easy casting rhythm, leisurely searching the water for a feeding fish before taking a step forward following each cast. Not only do I find this style of fishing relaxing but it can also be very productive at times, particularly when the trout move closer inshore.

However, fishing different reservoirs from the shore can also be heart-breaking and it soon became obvious to me that to achieve consistent success one had to be prepared to go afloat. To any observant angler, the disparity between the catches of bank and boat fishermen over the duration of a season is quite clear and at certain times there is nothing a bank angler can do to offset this imbalance.

When conditions are against the bank fishermen there is little hope of any sport, no matter how far one can cast or where one fishes. I remember days on Grafham when the trout would not come within 100 metres of the shore and we, the poor bank fishers, looked forlornly on as the boat fishermen took fish after fish.

Haphazard stocking policies don’t help the situation at all. It can be either feast or famine depending on the season or when the next injection of fish are stocked to liven things up. For bank anglers there is always the early season bonanza when a glut of fish can be taken following the main pre-season stocking. However, the easy harvest doesn’t last long and invariably there follows a lean period until the weather warms and the trout start to move on the surface.

In late May and June there is the chance of some sport if the conditions are good and of course there is always the evening rise to raise our hopes. However, July and August can be desperate months, unless there is a summer stocking, until the fish move inshore again in September. As much as I love fishing, I do go to catch fish. If I was to achieve that aim and catch fish consistently then I felt there was no alternative but to leave the bankside and go afloat. Besides, messing about in boats looked like fun, certainly preferable to suffering another blank day on the shore.

BOATS – THE BEGINNING

Boat fishing presented me with a set of new problems to solve. On each visit to a fishery, the problem would change with the conditions and the season. To anchor or not to anchor, slowing the boat’s drift or using a boat’s drifting bias to fish a particular drift effectively were factors that I had never encountered or had to consider before. I soon realised that success wasn’t guaranteed just because I had chosen to fish from a boat.

We did catch more fish, which was the reason for going afloat. However, our success was purely because we were over more fish. There were occasions when we could and should have performed better, if only we had a better understanding of boat handling. Our failure to make the best of certain situations through our lack of experience fishing from boats was, to say the least, frustrating. My boat handling skills were going to have to improve. I needed to learn the fundamentals of boat fishing so that, given a certain situation, I could fish with confidence no matter what the weather conditions.

Knowledge and confidence grew, but it took time and experience. At first we used to habitually anchor because that is what the majority of the other boats were doing. We did not give due consideration to the prevailing conditions or how to position the boat to take advantage of those conditions. It didn’t take long for the penny to drop. I soon realised that these factors were important and that they could make a significant improvement to our catches. Armed with this knowledge, we began to capitalise on the advantage of being afloat. Fishing from boats had far more to offer than I imagined and I was eager to learn more.

Northampton Style

The 1970s was a period when the majority of boats on English reservoirs and lakes were anchored, with only a few drifting Northampton Style, bow to the wind, fishing lures on the swing. With the exception of Chew, one rarely saw boats drifting broadside with two anglers fishing a short line in front of the boat, akin to the traditional fishing of Irish or Scottish lakes. This was a style of fishing that appealed from the moment I first saw the method employed.

Traditional Style

But none of my friends fished this traditional style, so I had no experienced, old hand to learn from. I was very much in the dark. Opportunities to fish while on holiday in Scotland or Ireland were seized, particularly if there was an invitation to fish with an experienced angler or local boatman. Fishing traditional style, short-lining with a team of wet flies, for this was the way one fished from boats on wild waters, was great fun and productive too. While out on these trips I would try to take in as much information as possible but when it came to methods, they seemed pretty basic and were not as complex as the reservoir techniques.

Tackle would consist of a longish through-action rod of cane or fibreglass, a floating line and a team of three or four wet flies spaced evenly apart on a fairly short leader. A short line was then fished in front of the boat. Some anglers would fish a short cast using the rod action in one continuous lift and a hand haul to move the flies. The length of the cast was limited to the working length of line that could be fished with the one movement. This kept the flies high in the water and on its day – preferably one with warm, balmy overcast conditions – it was effective. But the method itself was very restrictive.

Other anglers would favour a slightly longer cast which required a number of hand hauls before the rod was raised to lift the flies to the surface. This latter method, which was more versatile, allowed the angler to fish the flies through the upper layers and it was this technique which I adopted. A more productive method, it was this style of pulling flies, albeit on a short line, that has evolved into the modern loch-style methods we have today. Surprisingly, some of those early days resulted in superb bags of fish but I know now that luck played an important part. Never spurn luck!

Looking back, conditions always seemed to be perfect and the plan simple: just align the boat on a drift and fish a team of three traditional flies on a short line through the upper layer of the water. The method was simplicity itself. Casting a short line, pulling the flies back with smooth pulls followed by a long steady lift brought fish charging through the waves to seize the flies. Sometimes the final draw would entice a fish up from a deeper lie to make a head-and-tail rise over the top dropper.

Traditional drifting style was not only novel but great fun compared with the static boat fishing techniques we had adopted for the small reservoirs. Not only was it enjoyable, it was also effective for the wild browns. So I reasoned: if the method could take wild fish, why not reservoir trout? Also, with so few boat anglers drift-fishing broadside at this time on the reservoirs, traditional methods might give me an edge. It was worth a try.

The early attempts met with mixed results for several reasons which at first I did not fully understand. It was obvious that if I was to avoid further frustration, I needed to reassess my approach. Why was it that wild uneducated trout responded so well to the traditional tactics, but whenever I used similar methods on the reservoirs, my results were mixed? There had to be other factors involved.

Troubleshooting

I tried to rationalise where I was going wrong with my traditional approach. Firstly, I needed to consider the waters which, to my knowledge, were best suited to traditional boat fishing methods. To improve my confidence, a free-rising water was a necessity, which automatically ruled out one of the fisheries that I was familiar with and fished quite a lot at the time. Datchet, a deep reservoir, held some stunning trout but they required a more specialised deep water approach as the fish were poor risers. This and the haphazard stocking policies on some of the other waters could explain some of my early poor results.

As Rutland had yet to open, we were left with Chew, Draycote, Grafham, Farmoor and Pitsford. Of these, Chew was arguably the best water around for good quality surface sport but all these reservoirs could, provided you chose the right time to go, produce superb top-of-the-water fishing. And of course this was another point which I had in my eagerness overlooked. What was the best time of year or season for traditional wet fly fishing on the surface?

The author with a 5lb rainbow from Rutland’s South Arm.

Some fisheries produce good surface fishing earlier than others but in the main the richer lowland reservoirs do not produce well until mid-May or later, unlike some of the wild brown trout lakes that I fish where good surface fishing can be had from late March onwards. Grafham never really used to get going until June but once the fish began moving on the surface, the sport could be memorable. So here again we had simple fundamental principles to learn that anglers now take for granted.

Old-style traditional boat fishing on the surface of rich lowland reservoirs that are predominantly stocked with rainbow trout is largely a waste of time before the waters have warmed...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.3.2018 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Angeln / Jagd |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport | |

| Schlagworte | bloodworm • boat fishing • Corrib • dap • Dapping • drogue • emergers • Irish trout fishing • Lough Mask • mayfly • reservoir trout • Sheelin • wild trout |

| ISBN-10 | 1-910723-87-8 / 1910723878 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-910723-87-6 / 9781910723876 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 9,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich