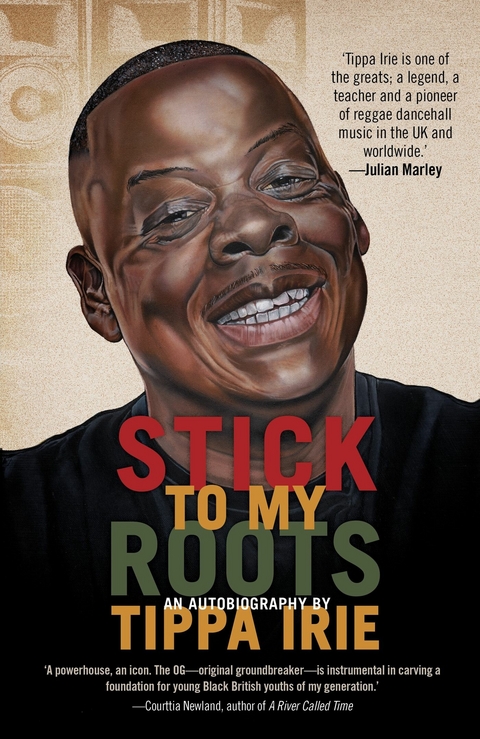

Stick To My Roots: A Music Memoir (eBook)

320 Seiten

Jacaranda Books (Verlag)

978-1-913090-85-2 (ISBN)

Tippa Irie is the Grammy-nominated artist most known in the UK and all over the world for his Reggae music. Tippa has worked with bands and artists such as Maxi Priest, Peter Spence, Pato Banton, Long Beach Dub All-stars, Jurassic 5, Friendly Fire Crew, Detour Posse, Chainska, The Uppercut Band, UB40 Aswad, The Far East Band and more recently Congo Natty aka Rebel MC to form a group called UK AllStars, David 'RamJam' Rodigan and countless others. Not just a successful performer, Tippa has also built up a reputation as a top radio DJ, record producer, and owner of his own studio. To date, Tippa remains one of the most successful entertainers to come out of the UK and continues to fly the flag for the UK scene wherever he goes. Stick To My Roots is his first book.

Tippa Irie is the Grammy-nominated artist most known in the UK and all over the world for his Reggae music. Tippa has worked with bands and artists such as Maxi Priest, Peter Spence, Pato Banton, Long Beach Dub All-stars, Jurassic 5, Friendly Fire Crew, Detour Posse, Chainska, The Uppercut Band, UB40 Aswad, The Far East Band and more recently Congo Natty aka Rebel MC to form a group called UK AllStars, David "RamJam" Rodigan and countless others. Not just a successful performer, Tippa has also built up a reputation as a top radio DJ, record producer, and owner of his own studio. To date, Tippa remains one of the most successful entertainers to come out of the UK and continues to fly the flag for the UK scene wherever he goes. Stick To My Roots is his first book.

Chapter Two

Born in the Dancehall

‘Newsreader’, ‘toaster’, ‘chanter’, ‘DJ’, and ‘Master of Ceremonies (MC)’… these were the dancehall titles that became a part of me. ‘Rewind selector and come again’, ‘“lickwood” mean “rewind” and “gunshot” mean “forward”’… These were the terms used for MCs in dancehall. The strong influences of reggae playing from within the doors of my family home, the vibrant tunes coming like my very best-seasoned Caribbean dishes, just like Mum’s cooking, the tunes from my dad’s sound system (the Musical Messiah)—the rhythms and vibrations of the music were built into my bones. The structure of reggae, the way it’s put together, made me feel good, and the music flowed constantly through my blood. The words of the songs ran around in my mind and the beat shook the inner parts of my soul.

I was hypnotically drawn to the energy of reggae music—played by our parents, on vinyl on the gramophone by day, and through the sound system experience by nightfall, as if an invisible friend had physically gripped me. Reggae enabled me to get a better understanding of where my mum and dad came from; we were being culturally schooled without even knowing it! Through the songs and messages conveyed by the artists, I was transported to the roots of reggae music, and it was being recorded subconsciously in the memory bank of my mind.

But reggae music belonged to us; it was our own pulsating heartbeat. It was our world. It taught us our history, delivered our very being to us from the essence of the songs, woven through hit after hit, tune after tune, in fine rhythms and the sweetest melodies.

Some of my favourite teachers included the Abyssinians, telling us to look towards Africa, the motherland, ‘a land far, far away’; Dennis Brown journeyed us to ‘The Promised Land’; Burning Spear boldly declared, ‘Christopher Columbus is a damn, blasted liar’—a very different story from what was taught to us in the history schoolbooks. Sadly, even today, our kids are still not taught about their culture. Mutabaruka chanted, ‘It nuh good fi stay inna white man country too long’; Pablo Gad warned us of ‘Hard Times’. Back in the UK, Reggae Regular asked us to travel on ‘The Black Star Liner’; Aswad affirmed that we were ‘African children living in a concrete situation’; and Matumbi presented ‘The Man in Me’.

Dancehall music sprang from the sound systems of Jamaica, tracing back to 1940s Kingston town. The first known clash occurred between the legendary, pioneering selector/DJ, the Chinese-Jamaican Tom Wong and his Great Sebastian sound system, against Jamaican police inspector-turned-DJ Duke Reid. The clash famously featured Duke Reid pulling a gun from each side of his waist and squeezing the triggers. He then shouted the war cry, ‘forward, forward!’ going into clash-battle mode.

The early producers and pioneers were Count Matchuki and the world-famous Clement ‘Coxsone’ Dodd. The Jamaican film classic The Harder They Come, featuring Jimmy Cliff, provides raw insight into the trials and tribulations of the early Jamaican dancehall sound system days. Our original MC dancehall forefathers were the top-ranking Daddy U-Roy and Big Youth.

Jamaica’s sound system culture later led to the formation of rap and hip-hop across the US. The rap nation just consisted of reggae MCs’ younger siblings. This emergence originated with Kingston-born DJ Kool Herc, stringing up speaker boxes in the Bronx back in the seventies and adapting his Jamaican selector and MC styles to his new home in America. He mixed a unique scratching sound and added a new creation called ‘breakbeat’. DJ Kool Herc perfected this sound, isolating the tunes and the drumbeat, and finally adding synchronised vocals. DJ Kool Herc brought the potency of his island’s reggae vibes into the streets of America, evolving and inspiring future generations and bringing forth the careers of great foundation rappers such as The Sugar Hill Gang, Grandmaster Flash, Grandmaster Melle Mel, Afrika Bambaataa and—my all-time favourites—KRS-One, DJ Premier, and Guru from Gang Starr.

It is obvious to me that Jamaica’s sound system culture is wholly responsible for giving birth to the combined sounds of hip-hop, techno, drum and bass, junglist music, and warehouse raves. That is the power of dancehall and reggae, moving infectiously through generations.

The literal building of a Jamaican sound system is another layer of my musical culture. This required skills such as carpentry and welding, fitting the grids, wrapping and backing the speaker sealed with rubber and lined with cloth. There were four columns with eight boxes per column, providing a sound wall of sixteen boxes. Traditionally, these were painted black, with 12- and 15-inch speaker sizes; the speaker walls were up to seven speaker stacks. The system would pump out up to 30,000 watts. The speakers were divided into high, low, midrange, bass, horns, and tweeters. This building process produced an impressive and towering five-way crossover system. The sound system setup enabled the selector to mix live aby dropping out the treble and bass, while spinning his 45s.

Once the sound was strung up, the power it produced shook the very ground you stood on, rattling your bones with palpitating vibrations right through your heart. I used to find it amazing how some guys could stand so close to the pounding speaker and not worry about their hearing. I used to run from it! I was lucky, because I would be stood up around the sound on the mic, not in front of the speakers. This powerful energy would shake the windowpanes of the house parties and the clubs. No one could ignore our reggae music when the mighty sound systems came to town. I certainly couldn’t. At the ripe age of sixteen I would often wait on the street corner, just in time to catch the sound system van coming. I would then try to befriend the soundman and volunteer to carry some speaker boxes into the venue—this, I knew, would guarantee me a free pass into the dance. Sound system sessions took place at venues such as 4 Aces in north London, Moon-shot in south-east London, Lewisham Boys Club, St Mary’s in Ladywell, Colosseum in Harlesden, Uppercut Stadium Forest Gate, Hackney Downs school, 4 Aces club in Brixton, Lambeth Town Hall, St Matthews in Brixton, Galaxy in east London and the After Dark club in Reading.

Dubplates were an essential part of any event, providing you with a competitive edge in a clash with an opposing sound. The small reggae labels and independent pressing plants would produce and master our white-label vinyl dubplates, and each sound system would invite a variety of different artists to sing over the dubplates. The selector always carried his record box inside, which would contain 7- and 12-inch dubplates amongst his exclusive collection of vinyl. The sound system possessing the freshest dubplates would rule the night, and the session.

Sound system culture is not merely a musical experience. Sound systems are like a religion, and dancehall is the church. The mixing desk is the pulpit, and MCs, mic in hand, replace the pastor. Educating the people with knowledge, passing the spoken word on to the congregation, reggae, just like bluebeat, rocksteady, and ska had in my parents’ time, became the religion of my generation.

Yet it was like I lived in two worlds, which made me laugh. Around the house I would speak in Jamaican patois with my parents, but when my mate Neil knocked and stood there, I reverted naturally to being the cheeky cockney chappie that the outside world knew.

At the age of thirteen on the way to school I would be chatting words, the lyrics buzzing around my mind in the playground; I was forever reciting. At times, my schoolfriends would look at me and wonder if I was right in the head. They would take a double check to make sure that it was just me rehearsing my lyrics again. In fact, I found myself mumbling words wherever I was. In my bedroom I would pose with my afro comb in my right hand, pretending it was a microphone. I was already famous in the mirror reflection, imitating my reggae idols, drawn from the word go by the influence of the original Jamaican MCs. They could take the mic and confidently ride the rhythm on version after version. It was poetry—lyrics that told a life story. Dennis Alcapone did it. Daddy U-Roy did it too with his tune ‘Wake the Town and Tell the People’. And Josey Wales with ‘Na Lef’ Jamaica’. And Tappa Zukie and Horace Andy with ‘Natty Dread Ah Weh She Want’. And Brigadier Jerry ‘The General’ expressing his pride for ‘Jamaica, Jamaica’: he did it too. These tunes motivated me to take up the microphone.

I began to immerse myself, practising. And the more I rehearsed, the better I got. I also started to develop my own identity. On the mic, I initiated a unique musical fusion: a London accent in a Jamaican DJ style. My family supported and encouraged me. My cousins started to comment, saying ‘Tony, you are getting good at this.’ My musical desire was so powerful, no one around me could deny my inner passion. Strict as my dad was, he still allowed me to perform on his sound system, Musical Messiah. Down in the shop basement, I would get in a sneaky practice when no elders were around. Eastlake Road is where my very first performing experience began.

Apart from home, the second-best place for me to...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 24.8.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Schlagworte | Autobiography • Black British music • black musician • British Music • British Music History • Caribbean Music • Carnival culture • Eddie Nestor • General Levy • grammy-nominated • King Tubby’s Sound • LGR record label • Memoir • music • Music Autobiography • Music History • music literature • music memoir • music theory • Notting Hill • Reggae • Saxon MC • Saxon Sound • Sir Lloydl • songwriters • sound systems • South London Music • World History |

| ISBN-10 | 1-913090-85-X / 191309085X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-913090-85-2 / 9781913090852 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 11,3 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich