Harry Peckham's Tour (eBook)

200 Seiten

Nonsuch Publishing (Verlag)

978-0-7509-5145-6 (ISBN)

Introduction

When in 1807 Robert Southey, purporting to be a Spanish gentleman, wrote the preface to his Letters from England, he began:

A volume of travels rarely or never, in our days, appears in Spain: in England, on the contrary, scarcely any works are so numerous. If an Englishman spends the summer in any of the mountainous provinces, or runs over to Paris for six weeks, he publishes the history of his travels …1

The present book is a good example of the genre to which Southey referred. It was originally published in 1772 under a typically overweight eighteenth century title—The Tour of Holland, Dutch Brabant, the Austrian Netherlands and Parts of France: in which is included a Description of Paris and its Environs. In common with many travel books of its time it took epistolary form; a device made famous by the French Huguenot François-Maximilian Misson whose Nouveau Voyage d’Italie had been published in The Hague in 1691 and translated into English four years later. Greatly admired by Joseph Addison, Misson’s book was much imitated. One of the most successful books of the type, Patrick Brydone’s Tour through Sicily and Malta in a series of letters addressed to William Beckford, was published in the year following the appearance of Peckham’s Tour.

Self-effacement was another frequently adopted authorial ploy, designed to stress that the writer was a gentleman and not a Grub Street hack scratching away in a garret. Edmund Bott, Peckham’s exact contemporary, declared that his book, The Excursion to Holland and the German Spa 1767, ‘must not be dignified with the magnificent title of Travels. A lounge it might very properly be called, as it was undertaken without any hope of instruction to the traveller himself or of utility to his country but for the gratification of his curiosity and for that alone’.2 Harry Peckham insisted that his letters ‘cannot do their author credit’ so that he was obliged to insist upon ‘my name being concealed’.

Although the book turned out to be a considerable commercial success, running eventually to five editions, its author remained anonymous until the fourth appeared in 1788 when he was revealed to be—

the late Harry Peckham Esq.

One of His Majesty’s Council and

Recorder of the City of Chichester

Christened Harry, not as some have assumed Henry, Peckham was the son of the Reverend Henry Peckham of Amberley, Sussex, later Rector of Tangmere, near Chichester. Henry was a kinsman of Henry ‘Lisbon’ Peckham, the builder of grandiose Pallant House in Chichester.3 A striking feature of the house is the stone birds on the gate piers; intended as ostriches, their appearance gave rise to the nick-name ‘The Dodo House’. The ostrich appears on the crest of the Peckham family’s arms and can be seen on Harry’s bookplate.

Educated at Winchester and New College, Oxford, of which he was a Fellow from 1761 until his death in 1787 at the age of 46, Peckham was called to the Bar in 1767, became King’s Counsel and bencher in 1782, died in his chambers in the Middle Temple and was buried in the Temple Church. At the time of his death he was Steward of New College, one of His Majesty’s Commissioners for Bankrupts and, as we have seen, Recorder of Chichester.

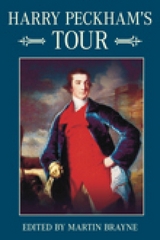

Harry Peckman was thus a successful lawyer but by no means a famous one, so that, whilst most of the principal events of his existence are not difficult to trace, it is harder to put flesh on the biographical bones. His book, of course, helps, revealing as it does a man of tireless energy and strong—if not always original—opinion. We know something of his physical appearance, for at about the time he graduated he had his portrait painted by the up-and-coming Joseph Wright of Derby. It is a swagger portrait typical of the day, so whether he was quite so handsome or cut quite so dashing a figure we must doubt. He does seem to think rather highly of himself.

The portrait is one of six painted by Wright for Francis Noel Clarke Mundy of Markeaton Hall, Derbyshire; they are of himself and five sporting friends. Mundy was a contemporary of Peckham’s at New College where he was a gentleman-commoner. Such students were invariably from rich families and were admitted in the expectation that they would prove to be, in the fullness of time, generous benefactors.4 The pictures were painted shortly after Mundy inherited Markeaton and each of the young sparks is shown wearing the distinctive livery of the private Markeaton Hunt.5 Although not averse to excessive drinking, Mundy was no Squire Western.6 He was also a poet, most famously the author of Needwood Forest (1776) and, after enclosure, The Fall of Needwood (1808). He was to become a member of the distinguished Lichfield literary circle which included Erasmus Darwin, Sir Brooke Boothby, Richard Lovell Edgeworth and Anna Seward.7

That the rakishness suggested by Peckham’s portrait had some substance in the man himself finds support both in the Tour and elsewhere in the written record. The Tour hints at a youngish man—he was 29 when it was undertaken—with an eye for the ladies; be it the ‘young, sprightly and handsome’ daughter of his Parisian landlord or the nude subject of a Titian painting or the celebrated statue of the Venus aux Belles Fesses in the garden at Marly-le-Roi. More conclusive evidence of the sowing of wild oats is to be found in his Will, drawn up on the 29 December 1784.8 Firstly, there is the French snuff box ‘with a saucy picture set in gold’ which he gives to a Chichester friend. Then there are some matters which must have weighed more heavily on the testator’s mind. We discover that he bequeathed an annuity of sixty pounds to Sarah Thompson, widow, and daughter of John Cooper of St Martin’s le Grand, London, as recompense ‘for an injury which many years since I attempted to do her’. We also find that his principal beneficiary was his daughter Sarah ‘born the third of May seventeen hundred and seventy one’. This despite the fact that nowhere, either in the Will or elsewhere, is a wife mentioned. One explanation, however, certainly presents itself; as a fellow of an Oxford college he was expected to be celibate and upon marriage his fellowship would have been automatically rescinded. We must assume either that he married in secret or that Sarah was born out of wedlock. Clearly he concealed, but did not deny, paternity. Alas, the Will was still the subject of a case in Chancery twenty years after Peckham’s death; the heirs of his executors fighting over their share of the spoils.9

We have another source of information which helps to fill out our picture of the author of the Tour. James Woodforde was another contemporary of Peckham. Born in the same year—1740—he too was educated at Winchester and New College. From shortly before going up to Oxford in the autumn of 1759 until a few months before he died in 1803, Woodforde kept a diary fascinating not as a record of great men and events, for he became a country clergyman, but for the remarkable wealth of quotidian detail of eighteenth-century life which it preserves. Peckham makes his first appearance in Woodforde’s diary—best known as The Diary of a County Parson—shortly after going up to Oxford when, on 6 October 1759 ‘Geree, Peckham & myself had a Hogshead of Port from Mr Cropp at Southampton.’10 How long it took the three students to consume the 57 imperial gallons which a hogshead comprised we cannot be sure, but Woodforde’s Diary suggests not very long.

In general the two undergraduates probably rubbed along pretty well together. Woodforde lent Peckham his ‘great coat and black Cloth Waistcoat’11 to go to Henley Assembly and, when the diarist was confined to his college rooms with an attack of boils, Peckham and another student ‘had their Suppers here and spent the Evening with me’.12 On the day after they had both obtained their fellowships they went, together with two others, to London. They visited Vauxhall, which Peckham in the Tour was to compare with a pleasure garden of the same name in Paris and, in the evening, they went to the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, to see All in the Wrong, a new play by Samuel Johnson’s friend Arthur Murphy.13 As we shall see, Peckham had a keen interest in the stage and in his book was to make illuminating comparisons between London theatres and those of The Hague, Amsterdam, Brussels, Lille and Paris.

However, although they often drank, gambled and played together, the relationship between future parson and future lawyer seems to have found expression in rivalry as often as in comradeship. On one occasion Peckham, a keen sportsman, ‘laid me that his first Hands at Crickett was better than Bennett Snr’s and he was beat’,14 but on another—

Peckham walked round the Parks for a Wager this Morning: he walked round the Parks three times in 26 Minutes, being 2 miles and a Quarter. Williams and myself laid him a Crown that he did not do it in 30 Minutes and we lost our Crown by four minutes. I owe Peckham for Walking—0:2:615

Although Woodforde sometimes had sharp words for fellow collegians he is rarely quite as critical as he is of Harry Peckham whose energy and ambition the somewhat slothful diarist may well have envied. He made no particular objection when the barrister-to-be sconced (i.e. fined) him, two bottles of wine ‘for throwing’ in the Bachelors’ Common Room16 but when they argued against one another in the Latin disputation which formed part of the degree examination, Woodforde dismissed his opponent’s arguments as...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 20.10.2008 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Historische Romane |

| Literatur ► Klassiker / Moderne Klassiker | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber | |

| Reisen ► Reiseberichte | |

| Reisen ► Reiseführer | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Geografie / Kartografie | |

| Schlagworte | 1769 • Amsterdam • Antwerp • Belgium • Brussels • Calais • commissioner for bankrupts • Culture • France • georgian • georgian era, georgian period, georgian society, calais • georgian period • georgian society • Ghent • harry peckham • harry peckham, king's counsel, commissioner for bankrupts, recorder of chichester, sportsman, tourist, tourism, travel, travelling, traveller, travel writing, letters, 1769, netherlands, belgium, france, society, culture, rotterdam, the hague, amsterdam, antwerp, brussels, ghent, paris, rouen • king's counsel • Letters • Netherlands • Paris • recorder of chichester • Rotterdam • rouen|georgian era • Society • sportsman • The Hague • Tourism • Tourist • Travel • Traveller • Travelling • Travel writing |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7509-5145-1 / 0750951451 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7509-5145-6 / 9780750951456 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 277 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich